“The man at the gate was alone. Armed militia stood before him. And yet, he did not yield…”

On 12 November 2025, I shared my experiences as a peacekeeper at Ghana’s National College of Defence Studies during a session on conflict prevention and mediation in peace operations. This story is drawn from that reflection. Benjamin Kumbuor, PhD, former Defence Minister, chaired the session. Emmanuel Bombande, PhD, was a fellow presenter.

I first served in the UN Interim Force in South Lebanon (UNIFIL) in 1979, after it was established in March 1978 by UN Security Council Resolutions 425 and 426, as part of the Camp David Accords (1978), following Israel’s invasion of southern Lebanon during Operation Litani.

I was then the Adjutant of Ghanbatt II, drawn from the Second Infantry Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel IGMK Kpeto. The Ghanbatt was initially part of UNEF II, deployed in the Sinai as Ghanbatt 10, with its headquarters at Camp Mitla and control of the strategic Gidi Pass. In the aftermath of the 1979 Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty, the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) was to replace UNEF II. So, a nucleus of Ghanbatt 10 was assigned to join UNIFIL as Ghanbatt 11 because Ghana had decided to rationalise its peace operations deployments and number them sequentially together.

My second tour with UNIFIL was from March to December 1984, when I commanded Bravo Company as part of Ghanbatt 22, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel AYK Disu, headquartered at Kafr Dunin, with company positions at Tibnin, Kafr Dunin, and Kabrika. Lieutenants Augustine Ansu, Iddi Zakaria and Tony Aduhene commanded my platoons.

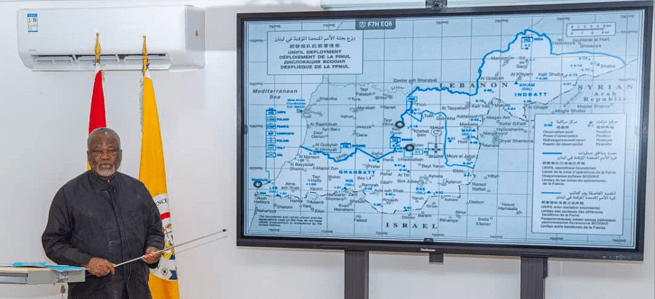

A photo of my presentation. Note that the map does not represent the actual deployment in 1984.

In 1984, UNIFIL’s mandate remained rooted in its original 1978 objectives:

• Confirm the withdrawal of Israeli forces from South Lebanon.

• Restore international peace and security in the area.

• Assist the Government of Lebanon in ensuring the return of its effective authority in the region.

But clarity on paper rarely matched reality on the ground, especially in the UNIFIL area of operational responsibility at the time.

On a Saturday morning, I was en route to the Commanding Officer’s durbar at Kafr Dunin when the radio crackled with urgent news. There was commotion at the Shaqra checkpoint—armed men demanding entry, voices raised, tension mounting.

When I arrived at the checkpoint, I found a lone soldier at the gate. Private Arthur—a former Junior Leaders Company (JLC) Boy—was holding his ground alone. The rest of the checkpoint team had taken cover. But not Arthur.

Facing him was Abdul Nabi, a local militia commander of the De Facto Forces (DFF), backed by armed men.

In April 1984, following the death of Major Saad Haddad—the Lebanese officer who founded the DFF—Major General Antoine Lahad assumed command and rebranded the group as the South Lebanese Army (SLA). During the Lebanese civil war (April 1975 to October 1990), the SLA collaborated closely with Israeli forces.

JLC was established in 1953 for the sons of soldiers aged 14½ years as a potential source of officers, NCOs, and technicians. They undertook both military and academic training for three years. Until it was disbanded in the wake of the 31 December 1981 Revolution, a total of 25 Boys Intakes, with an estimated 1,250 Ex-Boys, passed through the school before its closure. I was an Instructor at the School at the time and knew Private Arthur from then on.

Nabi was no ordinary soldier. He had a reputation: interrogations, abductions, disappearances—the kind of man who got what he wanted.

And what he wanted now was to enter Shaqra. “Open the gate,” Nabi demanded. But Arthur refused.

It should have been simple. One private against a militia commander with men at his back. The rest of the checkpoint team had already decided that compliance was safer. Even Arthur’s own Senior Non-Commissioned Officer (SNCO) had ordered him to let Nabi through. The easiest path was clear.

But Arthur held the line. He cited the mandate. UNIFIL’s mandate. The reason they were there. The reason the checkpoint existed.

When I saw what was happening, I knew it was not just about a gate. This was about whether the UN presence meant anything at all.

I made my decision in seconds, instinctively. I ordered an armoured vehicle forward and called for cover. The vehicle’s arrival was a statement—a show of force and of will. Nabi objected immediately, sensing the shift in power dynamics.

But then things escalated in a way that turned seconds into eternity. Nabi’s men, tense and armed, began unhooking their fragmentation grenades. Fingers moved toward safety pins. In that environment, surrounded by armed militia, with men holding live grenades, there was nowhere safe to hide. Hiding was not an option.

So, I did what a leader should do in that moment. I did not retreat. I did not negotiate from behind an armoured vehicle. I walked forward and engaged Nabi directly—by name. In that moment, I calmly said to Nabi, “Withdraw your men,” “Let them restore their grenades safely.”

Then I explained—not as a commander issuing orders, but as a peacekeeper explaining a mission. The mandate. The reason the checkpoint existed. Why it mattered.

And then I offered something Nabi probably had not expected: a compromise. “You can enter Shaqra, but we will escort your team.”

It worked. Nabi agreed. My convoy escorted him through the town and back to the checkpoint, where he exited into the Irish Battalion sector, where he had come from in the first place.

The checkpoint held. The mandate held. No shots fired. No grenades thrown. No bodies left in the dirt.

When the dust had settled back at company headquarters, reflection replaced adrenaline. I did what mattered just as much as the negotiation itself. I convened an immediate debrief with the men. And I commended Private Arthur. Publicly. Personally. I made sure everyone knew that standing by the mandate—even alone, even under pressure, even when ordered otherwise by armed elements—was non-negotiable. It was honourable.

Private Arthur was later appointed to the rank of Lance Corporal by the Commanding Officer, who also commended my action.

But the real lesson came later, in the quiet reflection that followed. The Shaqra checkpoint taught something that shapes understanding of peace operations: Strategic outcomes are not determined by generals in command centres alone. The Private Arthurs determine them at checkpoints, observation posts and patrols, holding ground even when surrender would be easier.

The professional guidance of battalion commanders shapes them, the steadfast leadership of companies that inspire, the gallantry of platoon leaders and SNCOs, and the admirable resolve of junior personnel on checkpoints and patrols—those with the moral courage to uphold their mandate, not because it is convenient, but because it is great… because it is right.

They are determined by the willingness to negotiate under threat, to see your opponent as a man with choices, not just an obstacle to overcome.

They are determined by systems that recognise and honour the men and women who make the difficult decisions away from the glare of the media.

But there was something else too—something more challenging to speak about. At the company HQ, my Company Sergeant Major (CSM) openly questioned my decisions and accused me of endangering the men’s lives. Why had I taken such a risk? Why not simply let Nabi pass? It would have been simpler. Easier. Safer in the moment.

It was a reminder that peacekeeping, for all its noble intentions, also carries temptations. Economic incentives. Self-preservation. The slow erosion of institutional purpose by personal interest.

It underscores the significance of the 2015 Kigali Principles, emphasising the active deterrent posture of peace operations in the implementation of their mandates to protect civilians.

The incident at the Shaqra checkpoint centred on key decisions: Private Arthur held his position; I chose negotiation over force; I recognised bravery; and I focused on the importance of mandates.

It was a story about what happens when ordinary men and women peacekeepers face extraordinary pressure and decide that some things are worth the risk.

It was a story about peace operations, the way they should work—not by force of arms alone, but by the force of clarity, courage, and conviction that the mandate itself is worth protecting.

This reflection is dedicated to the tens of thousands of peacekeepers—of all nationalities and ranks— who served under the UN flag in South Lebanon. As UNIFIL prepares to conclude its mission at the end of 2026, followed by an “orderly and safe drawdown and withdrawal” throughout 2027, its service stands as a testament to courage, restraint, and the enduring value of peacekeeping under the UN mandate.

Security Analyst, Colonel Festus Aboagye (Rtd)